What do we mean by 'killing' and 'letting die'?

By Ivar R. Hannikainen, Anibal Monasterio-Astobiza, & David Rodríguez-Arias.

Bioethicists have long asked how to distinguish killing from letting die. Opponents of the legalization of euthanasia routinely invoke this distinction to explain why withholding life-sustaining treatment may be morally permissible, while euthanasia is not. The underlying assumption is that, when physicians refrain from applying life-sustaining treatment, they merely let the patient die. In contrast, a doctor who provided a lethal injection would thereby be 'killing' them. At a broader level, this view implies that 'killing' and 'letting die' are terms we use to distinguish actions from omissions that result in death.

Theorists such as Gert, Culver and Clouser (1998/2015) advanced a radically different understanding of this fundamental bioethical distinction. In a germinal paper, they argue that to 'kill' involves a contextual assessment of whether the doctor violated a prior duty. In turn, whether the doctor violated their duty—namely, to preserve the patient's life—depends on the patient's preferences. (They actually argued for a more sophisticated view according to which only some preferences, i.e., refusals, constrain a doctor's duty—while others, i.e., requests, do not.) This view is qualitatively different from the first (what we call commissive) view. On this alternative view, which we refer to as deontic, 'killing' and 'letting die' serve to differentiate patient deaths that result from breaches of medical duty from those that do not.

How well does each of these theoretical perspectives capture people's use of the killing versus letting die distinction? In a recent paper published in Bioethics, our goal was to develop an understanding of the considerations that carve this bioethical distinction in non-philosophers' minds.

We invited a group of laypeople, unfamiliar with this bioethical debate and lacking any formal training in the health sciences, to take part in a short study. Each participant was asked to consider a set of three hypothetical scenarios in which a terminally ill patient dies, while we manipulated two features of the scenario: (1) the physician's involvement, and (2) the patient's wishes.

In some scenarios, the physician's involvement was clearly commissive (e.g., she administers a lethal injection) while in others it was clearly omissive (e.g., she does not engage a ventilator). For each of these scenarios, one group of participants evaluated a version in which the terminally-ill patient wanted their life to end, while another group evaluated a version in which they preferred to extend their life as much as possible.

Overwhelmingly, participants described doctors who disregarded their patient's wishes as ending the patient's life, even when they did so by merely withholding a life-saving treatment (see also Cushman, Knobe & Sinnott-Armstrong, 2008). Doctors who instead observed their patient's wishes were seen as allowing them to die, even when they did so through active means, such as administering a lethal injection. This pattern of results indicates that the deontic view captures the way people distinguish killing from letting die—while providing very limited support for the commissive perspective.

It stands to reason that a deeper understanding of medicine and human biology, or perhaps first-hand experience with critical care, could transform people's views about what constitutes 'killing'. Our lay sample lacked both, i.e., the understanding and the first-hand experience. In these circumstances, one might expect that their determinations would be grounded simply in their moral attitudes toward the doctor. So, how might the technical, medical concept of 'killing' differ from the lay concept?

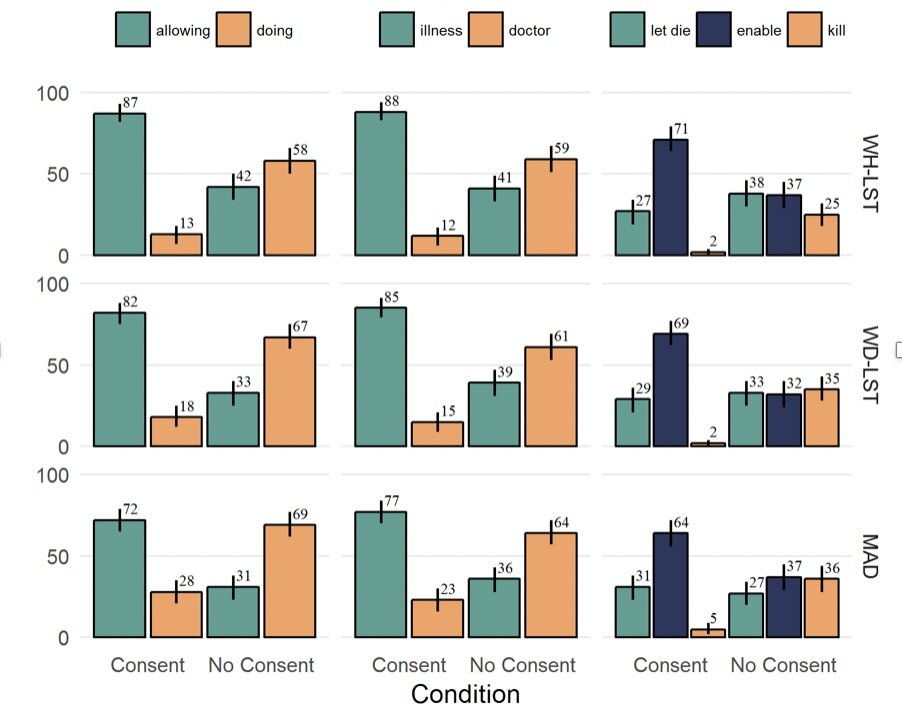

To find out, we ran the very same experiment on a new group, consisting of physicians, nurses, and medical students. To our surprise, this group of participants revealed much the same pattern. If anything, they provided even stronger support for the deontic view (see Figure).

Figure. Percentage frequency of each response by condition. Rows represent interventions (top: withholding life-saving treatment, middle: withdrawing life-saving treatment, bottom: medically-assisted death) and columns represent different questions (left: doing vs. allowing, center: causal selection, right: killing/letting die/enabling death). Note. Reprinted from "How do people use ‘killing’, ‘letting die’ and related bioethical concepts?", by Rodríguez‐Arias et al., 2020, Bioethics.

Beyond yielding a clearer empirical picture of the way people employ bioethical concepts, do these findings have any implications for normative questions at the core of medical ethics and health policy? Building on work by Joshua May (2018), the recent position statement on experimental philosophical bioethics by Earp et al. (2020) illustrates why they could, and how: For instance, some arguments against the legalization of euthanasia rest on the premise that commissive interventions constitute 'killing' while omissive interventions constitute 'letting die'. Together with the normative premise that doctors ought not to kill, this entails a clear prescriptive conclusion, namely, that medical ethics and policy ought to distinguish not providing life-saving treatment (which should be allowed) from euthanasia and any other commissive interventions (which should be forbidden).

However, the first premise is importantly at odds with evidence of people's usage of these bioethical terms: Participants—especially in our medical sample—treated commissive and omissive interventions indistinguishably, basing their determinations of whether a patient had been 'killed' purely on whether their preferences had been observed. Thus, these findings seem to undermine one of the principal arguments against euthanasia, and reveal a potential disconnect between the legal status of end-of-life interventions and prevailing attitudes toward them.

References

Cushman, F., Knobe, J., & Sinnott-Armstrong, W. (2008). Moral appraisals affect doing/allowing judgments. Cognition, 108(1), 281-289.

Earp, B. D., Demaree-Cotton, J., Dunn, M., Dranseika, V., Everett, J. A. C., Feltz, A., Geller, G., Hannikainen, I. R., Jansen, L., Knobe, J., Kolak, J., Latham, S., Lerner, A., May, J., Mercurio, M., Mihailov, E., Rodriguez-Arias, D., Rodriguez Lopez, B., Savulescu, J., Sheehan, M., Strohminger, N., Sugarman, J., Tabb, K., & Tobia, K. (2020). Experimental philosophical bioethics. AJOB Empirical Bioethics, in press.

Gert, B., Culver, C. M., & Clouser, K. D. (2015). An alternative to physician-assisted suicide: A conceptual and moral analysis. In Physician Assisted Suicide: Expanding the Debate (pp. 182-202). New York, NY: Routledge. (Original work published 1998).

May, J. (2018). Regard for reason in the moral mind. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Rodríguez‐Arias, D., Rodríguez López, B., Monasterio‐Astobiza, A., & Hannikainen, I. R. (2020). How do people use ‘killing’, ‘letting die’ and related bioethical concepts? Contrasting descriptive and normative hypotheses. Bioethics, online ahead of print.